“Fate Creek” is the third chapter in the novella-in-progress The Doll Sanatorium. In the summer of 1928, with a tunnel being blasted into Beaucatcher Mountain three blocks away and Asheville High School under construction just down the road, teenager Catesby Eleanor Wythe moves to Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House with her mother. Mrs. Wythe’s older, intellectual husband — Catesby’s father — has left the family, decamping from their stately home in Upstate South Carolina to join an artists’ colony out West, and now Catesby and her mother are trying to get by in Asheville as a family of two. Considered backward by strangers because of her shyness, her conspicuous aloneness, and her old-fashioned long hairstyle, Catesby is frequently in trouble with her impatient, hot-tempered mother. (In Chapter I, it’s implied that Mrs. Wythe has not emotionally recovered from the death of twin baby boys ten years earlier, during the influenza epidemic).

In Chapter II of The Doll Sanatorium, the residents of Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House gather for a card reading courtesy of a local mountain medium who calls herself The Dry Ridge Diviner. While her mother is having her fortune told in front of the fellow boarding-house residents — including Catesby’s new friend Jubal Justice, a young man who keeps the grounds at nearby Cliff Haven Sanatorium for tuberculosis patients — Catesby impulsively shouts out, imploring her mother to find out the exact address of her vanished father. In Chapter III, we discover what happened next, as Jubal Justice treats Catesby to a car ride in the countryside to visit a mountain swimming hole.

Chapter III: Fate Creek

Not all of them died. Rather, a lot of the folks at Cliff Haven did exactly what they were expected to do — that is, get healthy again, grow into competent breathers after prolonged exposure to the Blue Ridge climate. No matter the weather, they were bundled into their beds in the open sun room to inhale the mild, high air. An educated lot, most of them, they wrote flowing letters home. They claimed the air for themselves as though it were a tonic mixed personally for them by the druggist.

But the Mountain Cure was for everyone, advertised everywhere, available to all sufferers of tuberculosis: all who had means. The afflicted saw the pen-and-ink sketches of Cliff Haven Sanatorium, timber-fronted amid the heath, in full-page newspaper advertisements in Miami, in Charleston, in Atlanta. They came alone, if they were able, or were brought by nervous spouses or anguished parents or bachelor uncles or spinster sisters, to fill its long halls.

“I seen plenty walk out of there,” said Jubal Justice, who’d been keeping the grounds at Cliff Haven since the grass and vines had started growing up in April. Now, in July, driving his neighbor’s borrowed car, he was rangier than ever and deeply suntanned. The summer was as hot as it would ever be, and he was taking Catesby to wade in a place he called Fate Creek. A swimming hole.

“So I reckon it does work, sometimes,” Jubal Justice went on. “The Mountain Cure.” In profile his jaw remained rigid as a bear trap, but he delivered a chh-chh out of the corner of his mouth and then smiled at his foolishness. He was still more used to directing a horse than a machine. “Or maybe the lungs themselves git bored as heck just a-sitting there stock still.”

Catesby had brought food for the day: hardboiled eggs rubbed in salt and pepper and a jar of pickles the saintly Widow Arrington had slipped her, below-hand, at supper, in a widow’s resigned knowing way, plus a handful of butter cookies from her mother’s private tin and a blue Ball jar of sweet tea with a thick iron lid, all wrapped up like a baby in a brown paper parcel beside her.

Catesby Eleanor Wythe had made a picnic for two, and now she was trying to hold herself and the picnic still on the hectic seat of the Model A. Her legs and her backside still throbbed with cuts and bruises. A heavy wooden spoon had made the bruises; the cuts came from the cruel serving fork that belonged to the Wythe family silver. She remembered her posture and sat up taller — but then she might hit her head on the car’s roof.

“Yes, ma’am,” he went on. “All them sad old lungs yonder saying to themselves, ‘Might as well start living right like the other body parts so we can git the heck out of this prison.’”

She heard the cascade of giggles and reconciled them as her own. How long had they been locked away — since before her papa had left the family?

Jubal Justice had the day off. He’d traveled through town buying dried red beans and cake flour and white sugar for his mother and new embroidery needles for his sisters Ada and Patty Ray, who were both affianced and working on their bridal handkerchiefs. His youngest sister Mildred was going to have a birthday, and he had bought her a pair of hair ribbons, dark-green velvet.

“Our Little Bit, ten years old,” he said. “I swan. All of us Justices will be in double digits then.”

“They’re awfully pretty,” said Catesby, looking at the two ribbons that Jubal Justice had tossed gently in her lap for inspection. Mildred must still have long hair, then, the same as Catesby. She daydreamed of having her own braids cut off now, cut off all at once — a bob, finally. The unattached young ladies who crowded into the front foyer of Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House, elbowing one another and shrieking after the lone telephone, were all bobbed, and so were the girls her age, the ones who walked three and four abreast, strolling arm in arm on the sidewalk in front of Flora Sorrell’s, showing off friendship like a victory parade.

She supposed they had had their bobs forever. She supposed these same girls would go together to the new high school, come fall.

They turned ever more out of town. Jubal Justice steered the car with concentration down the length of a long dirt road that had no sign to mark it. Around each sharp bend the blue mountains came in close, the same hill again and again and yet all of them apart, too: a massive audience with different noses. Tranquil for now.

They were deep in the country. She couldn’t walk her way back to town now if she had to do it. Always in the week or two that followed the worst of her mama’s rages, Catesby became lighter inside, curiously reckless with a bravery that arrived airborne. Her night dreams of flying carried over into the morning hours.

Once the thing had occurred, she felt herself safe. Fine weather erased the storm and she lived day to day: what else could dare happen? She chattered at Jubal Justice in bursts of excited syllables.

In the days since the Dry Ridge Diviner had read cards on the white-painted front porch of Flora Sorrell’s, Mrs. Wythe had shown Catesby this other way to make eggs — boiling, cooling, peeling, and seasoning — taking over the stove and sink in the service kitchen for so long that boarders like old Hiram Ramey and pregnant Mattie Wilkinson started making remarks. Mrs. Wythe sassed and scolded and winked. Below their hearing, she hissed. But she would not make way for them.

For a whole afternoon they had sat, knee to knee, in rockers on the porch, the two of them, and her mama had set her up with a needle and thread and a length of muslin. She didn’t say a word this time about her daughter’s large, clumsy hands. So now Catesby could sew, a little. She began to make a sampler for her grandmama back in South Carolina.

She told Jubal Justice about the noisy birds that had settled a summer nest in the branch of a tree she could see from her bed at Flora Sorrell’s. (She was alone more now. When the weather was fine, her mama no longer held singing lessons in their shared room; instead, she had begun giving them on the gabled rooftop of the boarding house. If she could not find one of the male boarders around the place, Mrs. Wythe ordered her daughter to carry two chairs from the common dining room and squeeze them all the way up the cramped interior staircase through the little door that led, like a door in a dollhouse, to the third-story exit. She wrote out a new advertisement and trusted Catesby to walk it down to the city newspaper office: “Mountain View Singing Lessons: The Best Air for Your Best Voice.”)

“How do they call to you — in threes? Do they say ‘teakettle’ three times over?”

“Why, yes,” she said. “That’s exactly right.”

“Carolina wrens,” said Jubal Justice.

“Teakettle, teakettle, teakettle.”

“That’s it.”

If she told this young man she could not swim, he could not make her — not the way she was feeling today. He parked, finally, in a flourish of barking smoke, under a sycamore tree that leaned its branches with wide, hand-shaped leaves definitively in the direction of the creek. He delivered the picnic bundle from her care and sheltered it in the crook of his arm and came round to open the car door for her and help her down. He led her to the head of the trail that ran beside the water and then motioned for her to go in front.

It was her first time in a mountain wood, so full and bursting-fresh: a forest breeding its own green weather. Somehow, though, she knew these great trees better than she knew Jubal Justice. A ripe stink rose from the forest floor — nothing hostile. “Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful,” she said. That was three syllables, too.

Then she said: “My papa knows birds, too. I would guess he has a hundred books on plants and animals. You see, he’s a naturalist. A learned man.”

Jubal Justice nodded. “Sure enough. My own daddy ran a little store up in Haint Cove before he passed. Never took to farming. Some hold it again us cause my mama and sisters don’t have to string tobacco bags for money. He left just enough, you know, with me working too. And soon enough Ada and Patty Ray will be married off.”

“Do they call your mama the Widow Justice?”

“Ha, ha! Now that would be somethin. ‘Widow Justice’ — it sounds like a statue.”

“Or a warplane.”

“But no. You see, in our holler there’s too many like her to be marked out like that.”

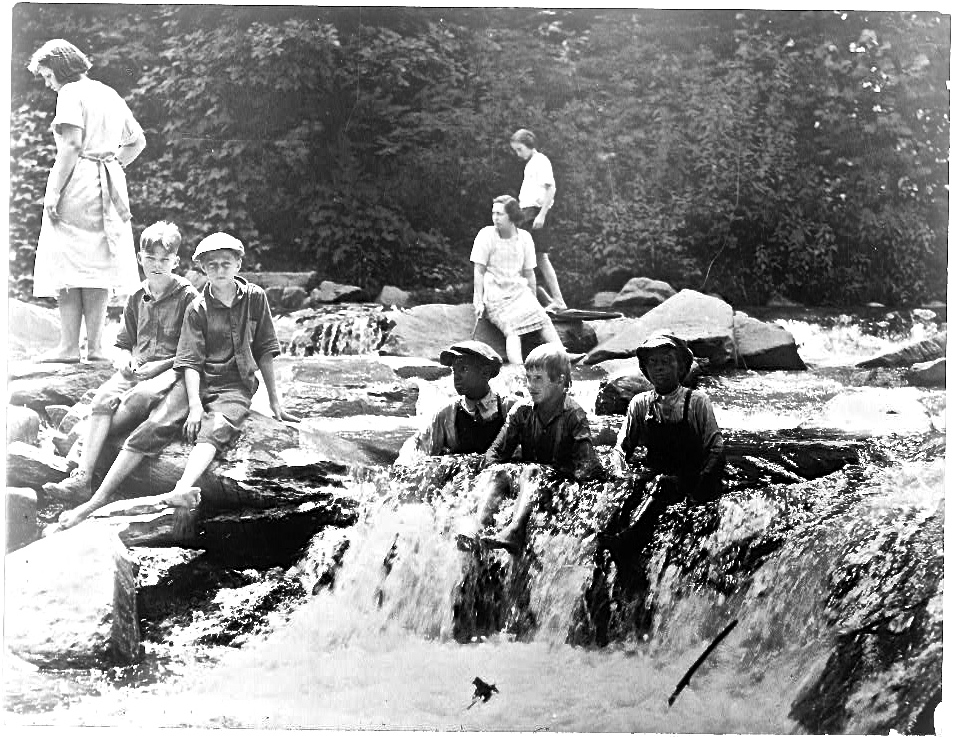

Fate Creek to their right was chattering too, white little rapids running over rocks and, in between, the clearest water Catesby had ever seen. They walked and walked, and after a while they passed the back side of a massive boulder that had another sycamore growing beside it, stretching and bending toward the water. After coming out of its shadow they arrived at a part of the creek that was stilled inside a pool.

The swimming hole was almost completely round. Jubal Justice said since he was so tall the shallow part hit him right at the chest. But Catesby was not so short herself — if she did not mind him saying so — so he expected she could keep her head above water.

Fate Creek was not the only thing out here with a voice. The hum-roar of the breeze, the mute shouting of the sun and the uprise of every insect, unrelenting, shrunk their own human utterings to little consequence.

“Begging your pardon,” he said, and his voice was close, but she had to think hard to hear him.

“I like being tall,” said Catesby.

When he went behind a tree and came back in bare feet, wearing only a white undershirt and white underwear to his knees, she removed her own socks and shoes. She went behind her own tree and took off her long skirt and spread it out on a sunny rock. Trembling, she unbuttoned her middy blouse and draped it over the skirt. The garments would keep each other safe.

She was left in her tap pants and camisole. Now that Catesby and her mama were bound to do all their own washing — handing in their ticket every week to take their turn at the wringer basin in a shed off the service kitchen — she was wearing her corselette as little as she could get away with. Underthings discarded were underthings that could not become soiled and have to be washed. It was awful enough to have to launder the rags of her monthlies in what felt like a public show, the shed a tiny theater where any man might come in and observe the evidence.

Out here it did not matter in the same way.

“Lord, but it’s cold!” He must be used to it, she thought, but he nodded and told her she was exactly right; he could not dispute it. He was standing in the water holding out his hands to her and she inched in, protesting, boldly slapping water in his direction. By the time she reached him she was up to her neck, and he steadied her. The sun warmed their exposed faces and arrowed off the surface of the creek.

The sweet, wild numbness of the freezing water on her torn-up legs and bruised backside, the little minnows skimming against her knees and toes — it was too sudden. Relief had arrived with no warning. It had come all at once. Catesby began to weep, trying not to be noisy with it. She had nowhere left to hide her face.

The forest in its glory did not mind, or even care. The trees did not stare at the specter of tears; neither did they rant or fret. As for Jubal Justice, he rested his opaque blue eyes against the most distant hill line. He took Catesby’s long braids out of the water, first one and then the other, and kissed the ends of them. He took her head in both hands and held it against his warm shoulder.

Back on shore, they shooed the bugs off the parcel of food and unwrapped the brown paper and had their lunch. The sweet tea was good and strong. “I made this, too,” she said shyly. “I’m learning all kinds of new things now that we have to make do.”

“It’s mighty good,” said Jubal Justice. “I saw your mama teaching you to sew on the porch the other day, and it got me to wondering something.”

“Oh, but first I have something to ask you,” said Catesby. “Tell me, please — if you can. Is it true — is the Dry Ridge Diviner a witch? Mama said, ‘We all know what she is.’ I don’t know, though. That’s the thing that got me to wondering myself.”

“A witch?” He scrubbed a hand in his wet hair — he had gone underwater in the deepest part of the swimming hole, turning a somersault for her entertainment. Now he lit a Woodbine from the pack he had kept dry behind a rock. “Nope. No, ma’am, she ain’t no witch.” He squinted sideways at her. “She’s only a Ramey — second or third cousin to Old Hiram, I reckon. She runs a brothel down the north end of Galloway Gap. That’s the truth of it.”

“Oh,” said Catesby. “Well, if that don’t take the cake.” It was Jubal Justice’s own phrase she gave to him.

“Listen to you, mountain gal,” he teased.

“I used to sleep outside,” she said suddenly. “Back at home. Our big house and yard — why, I had every place to hide you could ever think of, and when I ran out of places indoors, I took up a quilt and slept under the magnolias, and no one would think to find me until I didn’t come in to breakfast. Papa said I was stealthy as a possum.”

Her papa’s humor came through her then as though he were dead and she had summoned his spirit. “Say, Jubal! I daresay the Diviner’s not so good at running a brothel — not so good if she has to read cards on the side to make ends meet.”

His laughter was so great it hit the water. It rose up and roosted in the trees. Catesby busied herself rolling up the ruffled hems of her water-logged tap pants. The cotton britches had gone translucent.

Jubal Justice told her about bonafide witches, mountain witches. He called them granny witches. “They heal folks,” he said. “It ain’t nothin to be a-scared of.” Granny witches lived in the furthest of hollers and only ventured out to deliver babies. If you needed a curse lifted off you or an herb poultice cooked up to draw out infection, you had to make a visit to her cabin, and it was there the granny witch would cure you.

“But if you like, Miss Catesby — if you need me to — I know one that could make you a salve for all them cuts and bruises your mama laid on you. I could bring it to you.”

“No thank you,” she whispered, spotting an ant carrying a minuscule square of bitten-off leaf in its mouth, sharp as a weapon. She observed its journey and chewed her own thumbnail in sympathy. “I know I oughtn’t to have called out about my papa, not for all to hear. Not the way I did that day. Sometimes I just burst out with a thing — I can’t help it. There’s something wrong in my head that way. I humiliate her.”

Jubal Justice flicked the butt of his Woodbine roughly into the water. “Nary a one of us in that boarding house blames you,” he said. “Your mama ain’t winning any friends her own self, never mind what you say or don’t say when you take a notion.”

“But she’s much busier now,” said Catesby. “Going and going like she does. Word’s gotten out she has the prettiest voice in town. She has three voice students now, did you know?”

“I reckon she has a nice voice when she sings.”

“But say, what were you wondering about anyway — earlier?”

Jubal Justice was careful. He was not the first person she had known who could be called countrified. After all, her mama’s kin were Mackles from the sultry river bottom. She guessed the Mackles could boil up their own salves and poultices, too, if the need arose; it would be like them to do so. Catesby had an aunt, her mama’s unmarried sister Jettie, who had stayed for two years after the baby twins died. Aunt Jettie would still come around, sometimes, with dark glass bottles of tonic packed in a lumpy satchel and a stash of chewing gum.

“Never mind their pretty feathers,” Charles August Wythe would say drolly, meaning the women’s shared dark-red hair. Never mind their pretty feathers — God had tipped the scales to the finer sister, his wife who sang like a harp in human form and left poor Jettie Mackle to try and keep up like a squawking chicken.

But that wasn’t exactly right, either, because both sisters spoke their minds all day long. Mama and Aunt Jettie called one another other “kid” and tortured Catesby’s grandmama with their slang and rough ways.

Jubal Justice had a country voice, too, but his was pitched higher. It halted sometimes, considering its path: a mountain creek around rocks. When he asked what he’d been wondering — it was about Catesby’s papa and why he had left — he apologized first. He paused to point out a nearby tree devoured nearly in half, the work of a beaver; he wondered if it would ever rain that summer.

“There’s a new feller over at Cliff Haven,” he remarked after a spell. “I got to talking with him when I was trimming back ivy the other day. I was up there under the big sunroom, on the other side of the screen from him, you know. Most of them there are too stuck-up to chat, even when they’re feelin good, and I wouldn’t want to come near em, anyways. But he was lonely and bustin to talk to someone. So I found out he’s a painter. Before he got sick, he was gittin money to paint the landscapes all across America.”

Catesby explained that her papa was not like that — not a painter-artist. Not really. He had a camera he used every few months. Sometimes he just took photographs of the azaleas and rose bushes in their yard, but other times he went by train to set up his tripod and capture the low-country inlets and beachfronts in Beaufort and Charleston. He called himself the William Henry Jackson of the South, Catesby remembered — he said the swamp lilies and the cypress and the Atlantic Ocean were his Yellowstone.

“And he sketches, too,” she said proudly. In his library at home were his framed sketches of the little twins, in their first months of life, and of Catesby, back when she was a baby too, and sketches of mama as a beautiful young bride. He had drawn all of those pictures himself. He read all the time, so many books, and he wrote for hours in his stack of green leather journals. He had a little mandolin no one was allowed to touch, and he would play airs from Spain and Italy.

“I think New Mexico,” she said, “is the place you go when you’re an artist of everything.”

He was listening intently, eyes fixed and long jaw set. Catesby had never known such a listener. She cut off her talking and looked around, nervous suddenly as though a tree might fall down on them.

Jubal Justice said he reckoned they ought to head back to town. “The last thing in the world I aim to do is git you in more trouble.”