Chapter II: The Dry Ridge Diviner

According to Catesby’s mama, the Dry Ridge Diviner was a sorry old vamp. She was that, and she was other, less mentionable things.

It was true the diviner wore so much face powder it was hard to tell her age, though she kept her head tucked under a farm woman’s pointed kerchief and wore a fringed shawl printed with paisley from another century.

Mama pitched her voice to reach the three men behind her. “I declare! So much flour on those wrinkles she could bake us a cake.” The men were lounging against the white iron railing, working up jokes every few minutes.

In the quiet spaces, they commenced smoking.

“Well, we all know what she really is,” Mama said, accepting a light for her Woodbine. “But isn’t this a gas?”

She had taken possession of one of the rockers, and she patted the narrow arm of her chair and told Catesby to sit there. “I’m too big for that,” Catesby said under the surge of chatter. Mama’s eyes glittered for a moment, but she flipped her attention back to the crowd and fastened it there like a jeweled brooch. Catesby began to inch away.

She backed up slowly to stand against the side of the building, under the white-painted porch ceiling next to the door. She traced the cool stone behind her with her fingertips.

Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House was buzzing with folks waiting to get their fortunes told, and the Dry Ridge Diviner was bent over her folding card table. It had a cracked leather top and was set up with a stool on each side.

The diviner was hard at work. Mr. Thad Wilkinson, who lived with his second wife, young pregnant Mattie, wanted to see if they would be getting the boy he was praying for. Old Hiram Ramey was a lifelong bachelor who rarely came out of his room, set down low next to the boiler room. His room smelled curiously of rotting straw, and he carried the sweet stink with him wherever he roamed; that’s why he was bound to stay clear of the others. But it was said the Dry Ridge Diviner could contact the spirit world, and Old Hiram hoped to get a message from his sister in Heaven, who had cared for him all his life before she died and left him to fend alone.

The third fellow on the porch was a young man, Catesby’s friend John Israel, who tipped his hat to her when she came out with her mama. She nodded. She didn’t see him tip his hat to anyone else.

But he was friendly, a little, to everyone. He had a way of seeming part of the crowd and apart from it, too. Was he only there to weigh character, after all, like the butcher weighed this or that cut of meat? His expression registered any flimsy utterings the same as more solid talk. But if John Israel went away, he would only take what was useful to him. Which might be like any man.

Mama rattled a handful of dimes out of her drawstring day bag. “I’m getting my full twenty cents’ worth,” she said across two rockers to widowed Mrs. Arrington, a lady in her forties who taught school. “My girl can get the ten-cent special. You see how tall she is,” Mama went on, “but she’s just fourteen, and still as sweet as nine or ten. She’s not got enough troubles yet to warrant the full-price reading.”

For twenty cents, you got your cards read to you. For ten the diviner only traced your palms to sort out your heart and head.

“I say, she’s not got enough troubles yet to warrant the full-price reading,” Mama repeated. She laughed merrily at her joke, and the Widow Arrington was charmed. She rocked in agreement and offered an amen.

“Little Mrs. Wythe,” so they said about Catesby’s mama, “had been done wrong, way wrong” — so went the tenants’ gossip. “Husband gone Lord-Knows-Where?” — actually, to start an artists’ colony! Heaven knows what that might be. And across the country, no less, in the desert, somewhere unthinkable — could that be true? And was he a subversive, truly, or only goofy in the head? His wife left behind in disgrace with that strange child to raise, really a young lady. The girl should be out working, helping out — shouldn’t she? Not rolling up pill bugs and storing them in her skirt pocket or talking to herself, as some had seen her, up on the gabled rooftop, whispering things at the long blue mountain range visible to the southwest of town — that view that rolled end over end to eternity.

As her mama’s situation became more well known, Catesby found herself approached by fellow residents in the common dining room, where they had gradually begun to take their meals. “Be kind to your mama,” one or the other of them said. A few of the people living at Flora Sorrell’s had traveled down from the north. Their voices were peculiar — full of orders but brisk, rusty, like a mailbox left shut too long. “You, miss! Be a good girl for your mother. Hear? She’s had one lousy break.”

It was the middle of June now, and the question of school had dried up like the great blooms of rhododendron on the bushes lining the sidewalk in front of the boarding house. When they were in South Carolina, Catesby had gone to the female academy for six months of the year and had a math tutor at home during the off times. But mama hadn’t brought up the question of school in Asheville yet.

In their walk to watch the tunnel being blasted through Beaucatcher Mountain, Jubal Justice had mentioned a big public high school being built just down the road. Just a mile away, he said. He asked her if she aimed to go there next year. She said she didn’t know, but she tucked away “aimed” like she did other John Israel words. Holler. Yonder. Airish.

Catesby had told him about her school friend back home. “Sophronia Gibbes. We met because we had birthdays the same week. Have you ever heard of that?”

He said two of his sisters had been born in the same month, two years apart. But he never had heard of friends being born the same week.

“And this one time, when I went to her house for her party, they had made me a cake, too. That was the year we turned twelve.”

“That was mighty nice of them,” Jubal Justice had said.

“Yes, it was. She moved back to Charleston. That’s where most of her folks were from.” It was shocking, though, at the time. Leaving one’s home — every daily known thing. And now here she was, Catesby Eleanor Wythe, such a person herself. A girl who had been shaken awake one morning and made to move.

“That’s too bad, Miss Catesby. I bet you miss her.”

“Why, I do — but I believe she missed the sea and was glad to get back to it.”

Now she shook her own self, on the inside. She pulled her eyes away from the mountain, where they were always straying, and tried to attend what was happening. She had already disobeyed by not sitting on the chair arm, not pretending to be her mother’s little girl. She didn’t want to get scolded again for daydreaming.

***

A black mother cat with two lookalike kittens was living under the neighbor’s porch, and they came frisking out on the far side of things, behind where the Dry Ridge Diviner was sitting, to play in the dirt under the bushes. Catesby went and looked over the rail to see how the kittens were growing, and in that way she had a good standing look at the medium’s spread-out cards.

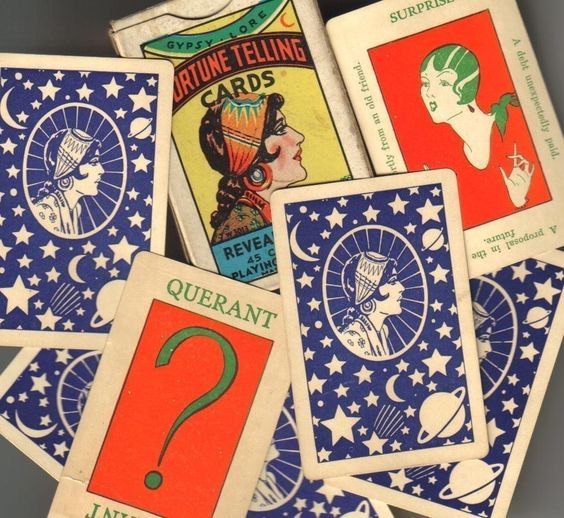

They were bigger, and more interesting, than the playing cards she had so often seen grown people use. These were like pictures from a fairy-tale book or her old children’s Bible, but more thrilling, drawn in scarlet and gold, full of folks dressed in robes and appearing courtly and wild. Their hair flowed like ocean waves, men and women alike. The title of each card was printed out at the bottom in letters like Roman numerals. The Lovers. The Fool. The Hanged Man.

The Hermit. It was Old Hiram Ramey’s turn, and after some gruff, familiar exchanges between himself and the diviner — it seemed they already knew each other, from somewhere, another time or place — he drew a card called The Queen of Pentacles.

The diviner immediately nodded, so Catesby knew The Queen of Pentacles must stand for Hiram’s dead sister. “She was salt of the earth, Hiram. Aye, she was. Too good for this world.”

Old Man Ramey’s eyes went soft with pain. “Can you see her?”

“I can, kindly. Yes — too good for this world. And likewise too eat up with hard work.”

“Well, what does she say to me?”

But the mysterious woman in the shawl and kerchief asked him to pick another card, in order to get the fuller picture. And when his time was up and he had to deliver his twenty cents, Old Hiram was disappointed and wanted to argue.

“And what are ye about, anyways, fooling with this witchery? I was up for a bit of fun, but this is pure devilry. Say, gal! What are ye fooling with?”

“Fooling with nothing, Hiram,” said the Dry Ridge Diviner. “Earning a living is what. Earning a living — just like you or anyone.”

“Earning a place in hell, more like.”

“Jealous fool. It’s not everyone’s been given this gift. Me, I was born with it.”

He and the diviner had the same accent, Catesby noticed. John Israel had the accent, too, but theirs was cut from an older rock altogether.

Next came Mr. Thad Wilkinson, who soon learned he would be getting the boy he wanted. He gave up his twenty cents easily and rose in a rush, clapping his hat back on and going inside to deliver the good news to pregnant, napping Mattie. The Widow Arrington was a known saint and she relinquished her turn to Mrs. Wythe, who patted her red hair with a flourish, took a stool, and set her lioness eyes straight on the Dry Ridge Diviner.

During Mama’s turn, Catesby walked back across the porch and down the front steps. She received John Israel’s unsmiling wink and went around to the side bushes to bend down among the cat and her kittens. She could not be seen, there, but she could hear the voices.

We all know what she really is. That’s what Mama had said about the Dry Ridge Diviner. But if she really was a witch, it would only make sense — that couldn’t be the secret. What else could the diviner be?

She had never told her mother about her walk to see the tunnel with Jubal Justice. That day, Mama was busy giving a singing lesson in their room; she had a new weekly client, an affianced young woman who wanted to increase her accomplishments. When they began trilling up the major scale, it was easy enough to disappear — to tiptoe downstairs and try to find Jubal.

And indeed, there he was, walking up the sidewalk, coming back to Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House after his day of work at the sanatorium. Catesby had raised her eyebrows and glanced in the direction of the tunnel, where echoing blasts could be heard until twilight. Jubal Justice had understood, had put out his arm for her, had taken her to see the action.

She had also never told her mother what she had done to poor Marguerite, her red-haired rag doll, after that one awful night during their first week in Asheville, that week when everything was raw and new and Mama was wild with nerves and forever grabbing Catesby, administering spanks and pushes, digging her nails in her daughter’s skin as offhandedly as she adjusted her own hair combs.

Now the warming sun was laboring to melt something. Catesby ran a finger over the mother cat’s bony head and decided she would not give her dime to the Dry Ridge Diviner. She did not want her palms traced by the old woman’s probing finger. Instead, if she could manage it, she would keep the dime for an ice cream and soda downtown. Maybe she would ask Jubal Justice to walk with her.

The kittens jumped on Catesby’s long skirt and tried to climb their way up. Kittens had claws, uncaring little needles, but one could share in their jolly triumphs. Kittens meant no harm. They were babies, after all, and she was their only mountain.

The bushes shielded her, and she listened. On the porch above her head, her mother spoke low and ferocious to the Dry Ridge Diviner about her vanished husband. Catesby heard Charles, Charles, Charles, hissed snakelike over and over. The diviner, too, was talking about a man. But not a human man — a man of myth. He was The Magician, from the first card Mama had drawn. Catesby heard the word “arcana,” which she did not know. She heard “power” and “desire” and “conceit.”

And she couldn’t bear it. She stood up with a purring black kitten in each hand and faced all the wrath in her world. “Good Heavens! Don’t ruin our chances. Just ask his address. Get the address, Mama!”

Everyone on the porch stopped to observe the big quiet girl suddenly yelling — here was entertainment with nothing attached. Smoke went up silently from the forest of cigarettes. Jubal Justice gazed at Catesby with his strange blue eyes, and then looked sharply at Mrs. Wythe.

“Ask her, Mama!” Catesby cried. “You ask her. Or else I’ll go in that tunnel yonder and I won’t come out.”