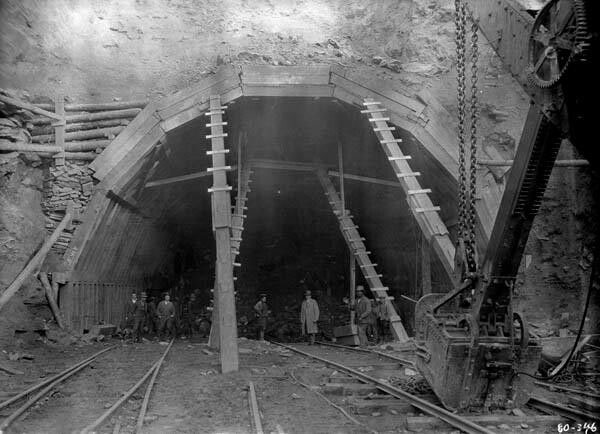

The year 1928 was momentous for Asheville and surrounding areas. Asheville High School was being built, Beaucatcher Tunnel was being blasted into the city’s downtown mountain, and an hour and more further west, the first phases of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park were under construction. In this fourth chapter of the novella The Doll Sanatorium, Catesby gathers the money and the nerve to get her hair bobbed and goes with Jubal Justice, her newly crowned beau, to his home in the countryside (near the Buncombe/Madison county line) to celebrate the sixth birthday of his youngest sister. All characterizations are purely fictional, including the depiction of the eponymous manager of Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House.

Chapter 4: Scripture Cake

Little red-haired Mrs. Wythe, less and less a professional mender of fine clothing, enduring possessor of a soprano voice from the realms of glory and rising local leader of fresh-air singing lessons on the balcony of Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House, was not, after all, the only enterprising woman in residence. There was Flora Sorrell herself, for instance, a scuttling lady, age obscure, who was widowed long ago, never to marry again.

But Flora Sorrell was frequently called away to care for her sick sister, Esther, helping nurse her rheumatic joints in the confines of her small house across town, set in a side street off of Montford Avenue and decently tucked away from that neighborhood’s stately homes and inns. At once distracted and one-track, Flora Sorrell was bound to materialize back at the boarding house a full day before the rent was due, hinting and grumbling, mixing personal threats with the Lord at the back of them, witnessing. Or she invented urgent, private conversations with one or another of the boarders so she could sniff a person’s breath for the wicked revelation of gin.

More lately, a new lady boarder had devised a plan for income. Mrs. Arthur Townsend, who was unexpectedly clever with hair, came to stay with her daughter Lily, who was just eight years old. And so, they became the second mother-and-daughter pair living at Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House, and as Catesby sat tall in a straight-back chair in their room, covered chin to lap in a heavy red-striped towel that was Mrs. Townsend’s own possession, not borrowed from the service kitchen, she was glad for the rain: otherwise this sudden robe would have smothered her.

The weather had completely altered its attitude. Into the bulge of late summer — all luscious ghastly weight; the mountaintops were the greeny-black of found jewels — there arrived, on no human authority, a week of showers that chilled both town and countryside. The rain blasted and squalled; parts of the day might even be called cold. The clouds rolled down and hung there, ringing the humped blue horizon like a white fur collar and obscuring the closer mountains altogether.

Catesby’s personal window had gone blank and misty. Even her nest of boldly quavering Carolina wrens was subdued. She wondered where they took cover. In the town square, where she now took walks alone while Jubal Justice was at work, the city pigeons would fluff up their feathers and appear twice their size — and yet stay still as tiny tombstones until these rages of rain passed over. This was how they protected themselves. But pigeons weren’t obliged to sing in the first place.

Mrs. Townsend was quick to say she had never had to work with her hands from any sort of expediency; her husband’s income was of surprising consequence, thanks to his gifts: his keen eye and his deft trained hand. It was just that she herself had a gift as well, really more of an instinct — she was untrained; it was just a knack — and there was no use letting her skill go to waste while her husband, Lily’s father, was taking the cure at Cliff Haven, obliged to lie still all day: a form of torture, to be sure, for any soul with a vigorous mind.

“Jubal Justice, who lives in town, he works at the sanatorium. He knows Mr. Townsend,” said Catesby. In her fists were her own two braids, two feet long, which Mrs. Townsend had cut off first, quickly, to halt any change of decision. Now she picked up a finer pair of shears from the dresser to shape the shorn dark remains into a proper bob.

Catesby had worried she might cry, once the deed was done. Well, she was lightheaded both ways — but nowhere near tears. “I declare, you must be proud to be married to a famous painter.”

“Oh why, yes, naturally I am,” said Mrs. Townsend. She was prim as a distant planet; her accent was a rejection of anything particular. “But we have been dragged from pillar to post, Lily and I, following Arthur’s dream. From the desert to the sea. I daresay he is famous, in his way, and it’s a blessed thing that his collectors remain faithful in this modern age. He has no taste for the abstract, you know. I call that style the death of good sense. And Arthur takes it even further, because that’s his way. He has that sort of flair — indeed he does. He calls abstraction the end of authenticity.”

“You all lived in the desert?”

“Oh my, yes, from the lowlands to the highlands, you might say, packing up every six weeks or so, no regular schooling for poor Lily to speak of,” said Mrs. Townsend, as though Catesby, because tall, was a species of adult: not a customer but a friend, a woman obliged to listen. “And here we are now, stuck for a while, aren’t we just? Arthur was just beginning his series on these eastern mountains, you know, when his cough became worse, and the doctor began to take on about Cliff Haven. ‘The best place for him, and so beautiful and restful for the mind.’”

“I find it so,” said Catesby. “I mean the mountains themselves. I’ve been to a swimming hole and to see Beaucatcher Tunnel, but never to Cliff Haven.”

“Oh, mercy — the hellacious noises coming from that tunnel! Shocking. And they’re busy blasting all those roads into the Smokies for the big park to come, as well,” said Mrs. Townsend. “But the government was going to grant dear Arthur a pass to some of the trails at sunrise and sunset, in between the chaos. A private view, you see. That’s how much they thought of him, and still do.

“Oh, it was going to be grand,” she went on. “And it may well prove so, if only he can get out painting again by the end of autumn. You see, his case isn’t so very serious, and we have a great deal of hope we won’t be here long. The doctors are speaking in terms of months — not years like some of those poor creatures trapped up in there.”

“Yes, ma’am.” Catesby had run out of responses. You weren’t supposed to make any unapproved marks on the walls at Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House, but, nevertheless, Mrs. Townsend had hammered up a large square mirror with silver trim, ornate and outsized next to the weak drop light that came with the room.

Catesby was looking at a face that had come to life, the same as a monster or a flower. A few freckles stood out: the only part of her mama she could ever claim. Her high, meek forehead now had bangs swept wavelike across it, which made her eyes the important thing: they appeared larger, much larger, two pleading shouts of brown. Her nose looked larger, too — but it was the Wythe nose, fully formed. And her chin, so exposed, looked as set, straight-on, as the jaw of Jubal Justice, except it curved in a soft way when she turned to observe her new profile.

Her neck was not a girl’s neck anymore. It appeared as long as a real young lady’s. She could no longer be kept down, stuffed back from life — could she? One of the nosier northern boarders liked to remind her she must enter the vast new high school in a few weeks: after all, it was the law, and furthermore, said the nosy boarder, Catesby must march down there and register her own self if that spitfire little mother of hers was too busy to do it. Sure, don’t be a mouse about it, laughed the boarder.

Well, Mrs. Wythe was too busy. She was away now most days, down to the square and even beyond; she did not always reveal her destination or even come back before dark. Except for an impatient push, here and there, or a sharp word about neatness, she had not laid hands on Catesby since the sickening row after the tarot reading. She did not even seem to see her daughter, most days, which was new: maybe better. Most mice aimed to stay undetected.

And Beaucatcher Tunnel, just three blocks away, was rounder and higher and more human-shaped every day. Catesby learned it was named after the mountain it was carved into, that was being exploded to make it.

And one day soon would come a park in the Smokies, which Jubal Justice said were the biggest mountains around. A park — but not with benches under the trees, as in the town square. Why, if they began building benches among the trees in those mountains, they would have to keep building them until kingdom come. And not a park with pigeons, surely, who could barely stir themselves to fly unless some kind person crumbled a cookie at them.

“Keep still now,” whispered Mrs. Townsend, who was shingling the back of her creation. The scissors were cold against the back of Catesby’s new, long neck.

Finally, the hair artist stepped away. “Well, well. You are a fine one, indeed. You put me in mind of a Botticelli — such a long face and full mouth. A classical face. You must favor your father, dear.”

“Why, yes,” said Catesby. Her hands were shaking, but a glance in the mirror at the bob made her braver. “I always have, Mrs. Townsend, not just today. Everyone always said so.” She thanked the young mother over and over and from her skirt pocket she handed over the dimes she had collected. She had a job now, herself. Miss Flora Sorrell was paying her to stitch up the shabbier of the cotton napkins that the boarders used in the common dining room to wipe their gossiping mouths.

***

The day Mildred Justice of Haint Cove turned six, Catesby rode in the old Model T with her beau — for surely that’s what he was, now. (He had kissed her on the lips on the deserted front porch of Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House in the foggy dark, steadying her against worries of absent mother, of looming school, of giddily bobbed hair, of cold fog descending into the hottest month like a ghost summoning words.)

Catesby held the birthday gift, her own idea, wrapped in her lap. She was a beau catcher, too — wasn’t she? She had a new nickname, after all, a buzzing little treasure that had never occurred to anyone else before Jubal Justice had said it. She had cut off the end of her best skirt for the birthday party, though not shockingly short, and hemmed the remains to the precise middle of her calves. Catesby fashioned the remnant, midnight-blue cambric, into a new dress for her main doll Marguerite, whose red yarn hair she had sawed off so long ago, with the best Wythe serving knife — was it only two months back, was it really, or actually a bygone age that might come back in a bad dream?

The quiet bald doll had been living under the back porch, a companion to the family of black cats and the roly-poly bugs, waiting mummified in a towel that Catesby had stolen from the kitchen, hidden away in the days before she had a young lady’s exposed long neck and a beau whose own name rang out like music and rescue. When Catesby took her out again, Marguerite smelled of soil, like strange little striving plants — like that whole summer’s reign of dewy, unfaltering green.

A few days after the haircut, unbeaten, Catesby asked Mrs. Townsend if she might have a tube of glue. In between their two narrow beds, instead of a privacy screen like the one that separated the beds in Catesby’s room with her own mama, Mrs. Townsend and Lily lived surrounded by stacks of metal tackle boxes containing pinched-up paint tubes and vials of turpentine and trunks of rough wooden scraps and tools for framing: all the art supplies waiting for Mr. Townsend, professional artist, once he was released from Cliff Haven.

Mrs. Townsend helped Catesby shape the fringes of her shorn dark braids into a little bob for Marguerite: a wig of real hair. “This is going to a little girl in the country who’s having a birthday,” Catesby said to Lily. “But I aim to give you something, too, soon enough,” she added in the accent of Jubal Justice. On the days the sun shone, Catesby’s last dolls, her miniature celluloid family of four on the windowsill, seemed in danger of becoming bleached. If Mrs. Townsend would give her some scraps of wood, Jubal Justice might show her how to make a bed for them.

She asked him now, in the car.

“I will absolutely make you a bed for them little dolls, Bee,” he said, and Catesby pressed her face against the inside of the car window to hide the lawless spread of her smile.

They curved north out of town down a road turned to slop by the rain. The road had so many sharp, separate twists it was like bits of a flailing snake someone had tried to hold together. This was as far away as the swimming hole, but in a different direction. The mountains became steeper, for a few bends; then they seemed to roll slowly back into the distance.

Then came a valley with a different look. Catesby saw stretches of fields between the weathered buildings, some with grouping of plants that looked like rows of small tents. Finally, with a rough bark of black smoke and a quacking honk, Jubal Justice pulled away from the road and cut the car off at the bottom of a low hill into which a car-sized space had been cut and a stone wall piled up to support it.

Catesby had expected a log cabin, though she did not say so. But the Justice family lived in a small, plain, white house covered with creeper on one side. The top floor of the house was not a full story high, but appeared like a hat with a jaunty brim, set down just under the roof. Like a room jutting out of a dollhouse.

The same stones that made the wall at the bottom of the hill formed an outdoor stair with no railing. “Careful, Bee,” said Jubal Justice, taking her elbow. At the top was a front porch lined with different-sized rocking chairs. A laundry line was strung between two old oaks at the left of the house, and on the other side was a vegetable garden full of staked tomatoes and whorls of fuzzy green vines from summer squash and big, fanning leaves: the beginning of pumpkins.

Further back, sitting statuelike on their little plots, were a covered well and an outhouse, whitewashed the same as the main house. They walked up the stairs of the farmhouse and crossed the porch. Jubal Justice shouted a birthday greeting and opened the noisy screened door for Catesby to walk through.

The big room was dominated on the right side by a woodstove and dry sink below high cupboards. A wooden dining-room table with pew-like benches filled up the middle, and on the left side, under a pair of glass windows that let in the room’s only reliable light, was a hard-looking sofa covered by a worn quilt, another rocking chair, and a very small table with an oil lamp. The rag rug on the floor was woven of four or five cheerful colors. A hall ran back into a distant bedroom; also in the hall was the bottom of a narrow stairway leading to the dark upper level.

In her papa’s copy of Wood’s Popular Natural History was a drawing of baby possums clinging to the back of their mother, a huddled grouping with a row of keen identical eyes. That’s just what the Justice girls were like, coming out from behind their mama in a stream of wild shyness that had in it no part of self-doubt. Their reserve didn’t last any longer than it took for the littlest one, Mildred, to scale up the length of her tall brother and receive a kiss on the cheek.

Ada and Patty Ray said they were almost seventeen and almost sixteen and asked how old Catesby was, half to her face and half to the air. She shifted her package to one arm so she could clasp their hands, two dry squeezes. They wore similar Dutch-style bobs and gingham dresses and had a rivalry in their bright cheeks that suggested the source of their health. Small Mildred wore the same dress in miniature, her long hair tied halfway up on both sides.

Mrs. Justice was small and proud next to her oldest son, her grown boy. She wore her hair in a bun, and she wasn’t inclined to blink.

By now, Catesby thought, she should be used to the Justice eyes — the blue not bright but closer to moonlight or rain puddle, the color an unlikely occurrence but repeated over and over. She was surrounded by them.

“I’m glad the rain stopped for the little one’s birthday,” she said to Mrs. Justice.

“I reckon we all are,” she said. “Glad to have ye, in any case. We’re plain out here, but you can see my girls all wear shoes.”

“Why, of course they do.”

“But only mine are birthday shoes. Brand-new — look here.”

“My, how lovely,” Catesby said to the little girl, peering down but forgetting to look up again. She set her eyes too long at the dark little shoes; she was looking through them, and her cheeks grew warm. The close room made her dizzy. Probably, because of how she’d been raised, they thought she was rich — of course they did — the old homeplace in South Carolina with the kingdom of magnolias, the parlor and the sun-drenched sleeping porch and all the rooms papered floor to ceiling and the large W.C. with the good high toilet safely located inside, on the second floor. How could they know?

But they must know, too, that that was her old life — that she now lived in one room, a room she had to share with her mama, and that she hadn’t a daddy, either, same as them — not one she might see or talk to. How much had Jubal Justice told? She could feel him close; yes, there he was with his arm around her shoulder. The package in her arms felt too big, and she wished suddenly she had let it drop out the car window and roll down into a ditch.

Maybe Mildred, her tow head adorned in the green ribbons her brother had bought for her in Asheville, would be insulted by a hand-me-down doll. Catesby studied the wide planks of the floor for a revelation.

She was spared her brief wretched reverie by the natural intensity of the large family. Brooding was lost in a sustained rise of voices, a complicated sing-song of giddiness and complaint. They talked about a neighbor, a fool of a man who was loved, who was hated. Apparently he had gone after trout in the high river and had netted instead someone’s lost valise. The loved-and-hated man had kept it on his porch for a full week, protecting it with his shotgun, bragging to folks that it was full of bootleg money, had to be — dumped by a gangster — only to find that the rotten brocade bag was crammed with nothing valuable: only a strange lady’s ruined underwear.

“If that don’t take the cake,” said Jubal Justice. Catesby didn’t know he could laugh so hard. Her heart beat fast.

“I believe that’s our cue to sit down,” said Mrs. Justice, when Mildred began chattering about her own cake.

Someone took the birthday package from Catesby and set it on the long wooden table where there were Black-eyed Susans in canning jars, a brown unfrosted cake, and cards to Mildred drawn on brown paper with hearts and stars.

Ada was tall and lanky like her brother, dark blonde, and Patty Ray was plump and lushly pretty with the shortest bob: it sat on her head like a shining cap. They were sassing vigorously about their upcoming weddings at the church, one set for late October and the other for Christmas week, after their birthdays. They made their eyelashes flirty and looked at Catesby sidewise. “I’d have rather been married in summer, but Nathanael is still cropping,” said Ada, “and will be for another week or more.”

“My fiancé Graney don’t farm,” said Patty Ray. “He’s trying to get Uncle Zeb to take him on at his pharmacy in Marshall.”

“She’s speaking of my late husband’s brother,” said Mrs. Justice. “There’s no pharmacy to speak of, yet. Zeb hopes to have one in the same place Laird kept the store, once. Laird was their sweet daddy.”

“Graney don’t farm because he ain’t cut out for hard work, not because he’s got him some bright future. That boy is a mess.”

“Now, Jubal…”

“Oh, Mama, let him talk ill about Graney. Like I care.” Patty Ray kicked the table leg. “If that ain’t the pot calling the kettle black, though. You with a job in town, and a place in town, and a car to drive, and lacking nary a thing … Ain’t exactly suckering tobacco yourself, hey, Jubal?”

“Can’t a brother look out for his own sister in this fast modern age?”

“Y’uns hush before I take a switch to ye,” said Mrs. Justice. “Quarreling in front of company. I swan!” But one corner of her mouth was turned up, and her pale Justice eyes seemed forever fixed: set too still to flash, or to court nonsense.

Catesby laughed a little, then, and Mrs. Justice nodded her approval. “Not a one of them too old to switch,” she said. She was pouring a cold drink from a brown stone pitcher into their tin cups, and Catesby learned it was sassafras tea.

They all sang Happy Birthday, but after the familiar song was over Catesby was again at sea. Mildred said it was Scripture Cake and that she had helped make it herself.

Patty Ray was the boldest. Catesby felt her face being studied. “It seems your friend’s not heard of Scripture Cake, Jubal,” she said.

He patted Catesby’s hand. “Ain’t no law against that. She’s here to enjoy, not be quizzed.”

“It reminds me of Christmas cake,” said Catesby. She cleared her throat. “I — I reckon.”

“One cup Judges, Chapter 5, Verse 25,” said Mildred. “That’s the butter. One and one half cups Jeremiah, Chapter 6, Verse 20. That’s the sugar.”

“Don’t show off, Millie-girl,” said Jubal.

“Four eggs,” said Mildred. “Jeremiah Chapter 17, Verse 11.”

“It figures like this: ‘As a partridge that hatches eggs it has not laid, so is he who gains his riches by unjust means,’” Ada recited. “‘In the midst of his days, it will forsake him.’ That’s the Jeremiah verse. Did you hear the eggs part?”

“That’ll do,” said Mrs. Justice. She passed Catesby a plate, also made of tin, with a large slice of the brown cake. “We go to the Methodist church over yonder near Sorrell’s farm. You passed both of them on your way here. Laird helped build that church himself, the same year Ada was born. Where do you worship, sweetheart?”

“Sometimes I used to go with my grandmother to First Presbyterian,” said Catesby. “In Greenville, that is.” She wanted to ask if Sorrell’s farm was related to Miss Flora Sorrell who came for the rent every month.

“Mama, may I ask Catesby how many brothers and sisters she’s got?”

Catesby laughed. “I’ll save you the trouble, Mildred. I don’t have any. Not any more. I had twin brothers for a little while, when I was even younger than you. But they died of the influenza.”

In Catesby’s house in Greenville, gifts had been more important than church. They were given and received in solemnity, unwrapped in the parlor for birthdays or in the great room in front of the fireplace, one at a time, at Christmas, extracted carefully from the pile beneath the decorated fir tree. When she had first received Marguerite, years ago, Catesby’s mama had told her how hard it had been to find the correct color yarn for her red hair, and said she hoped Catesby would take better care of Marguerite than she did her other dolls. When her papa selected a book for Catesby from his private library, as he sometimes used to do, wrapping a ribbon around it and inscribing the inside, with his private fountain pen, “To My Dear Daughter,” she was expected to lay aside anything else she might be reading and devote herself to the special, chosen book. Charles Augustus Wythe had bestowed jewelry, too, bowing like a prince in the performance of it. “To Leona of the Golden Voice,” he would say to his wife, presenting a small velvet box with a gold bracelet full of tiny charms. And Catesby would clap and exclaim as though it were for her.

Now she watched as Mildred tore the new, bobbed Marguerite out of her parcel and set the doll immediately on her lap. There was no exclamation of gratitude from the child, nor any distaste on her face — just a natural taking in, a breezy presumption, haughty but harmless, like a pigeon in the town square accepting a piece of cookie. She handed the crushed paper to Jubal and he jogged his youngest sister at the elbow, signaling to her to acknowledge the gift. But he was also busy telling his mother about the great height of the sunflowers he was obliged to keep staking and re-staking at Cliff Haven for the patients to enjoy. He told her he’d plant her some at home, too, if he could get his hands on some seed.

“Seven feet high! I swan!” said Mrs. Justice. “That’s kindly like Jack and the Beanstalk, isn’t it?” she said to Mildred. To Catesby she said, “I surely am sorry to hear about the little babies.”

“Why, it’s all right,” said Catesby. “Sometimes I think I can see some little blue blankets, far back in my mind’s eye. But it could be my imagination. I don’t remember the twins at all. It’s my mama.”

“Still a-grieving?”

Catesby said of course, thank you, to a second piece of Scripture Cake. “Yes, ma’am. She will never get over it.”