The makeshift recording studio on the roof of the Vanderbilt Hotel was hot as blazes. It was already steamy enough outside, hot even for August, and being up on the roof got us that much closer to the sun, as I figured it. Walt and I had traveled by foot, wagon, and automobile to get to the session in Asheville, so I thought I knew the sweltering heat intimately. But no, it was even hotter up there on the rooftop.

I tried to conjure the image in my mind of Walt and me as kids, holding hands, about to jump off a high rock into an ice-cold swimming hole. It was the best feeling on a hot summer day — that fathomless, green, soul-chilling water.

Why the studio was on the roof I don’t know. When Walt heard about the session — that Okeh Records from New York City was looking to record hill musicians at the Vanderbilt Hotel — we both imagined men in well-cut suits and women with ropes of pearls setting up a Victrola in the grand ballroom. Not that Walt or I had ever been in that ballroom or any other. We both were born and raised over east in Waynesville where Walt was a farmhand and I kept house for a couple of families. We’d grown up in Frog Level, a little neighborbood of new buildings, all of which I knew by heart. Our father’s store had been there, though we no longer owned the property.

Both Walt and I had a dream. Not exactly the same dream, but two dreams connected. His was to become famous enough from his music that he could travel around playing concerts for admiring folks in all fifty states. Mine was to get out of Waynesville, and I could see no real way to do it on my own, so I was hoping to hitch my cart to Walt’s rising star.

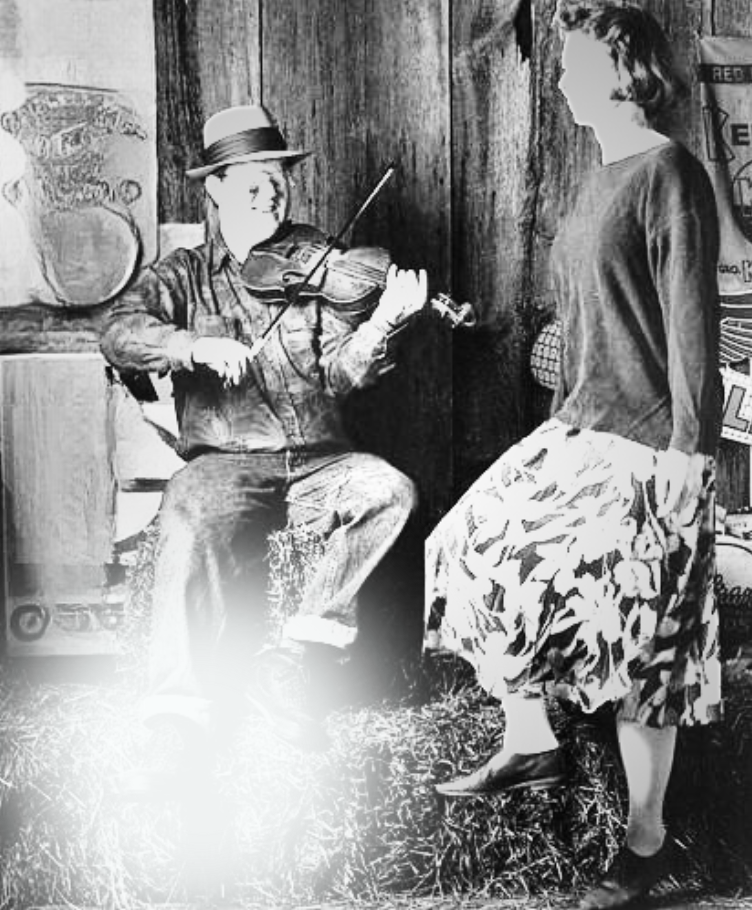

Walt was a fine fiddle player — had been since we were young. I remember our granddaddy giving Walt a fiddle when he was about seven years old, though I wasn’t but three myself. Since that day, if Walt was playing, I was right there by his side, flat-footing and singing harmony. Neither Mama nor Daddy would have thought much of me dancing and singing outside of home or church, but they’d both passed on — Daddy from the Spanish flu seven years ago and Mama last year of consumption.

We came into Asheville in a black Model T driven by a businessman from whom we’d hitched a ride. “You take care of this little lady,” he said to Walt, who replied, “Yessir.” I went red with embarrassment, realizing the man thought we were a young married couple, not brother and sister. But you couldn’t blame him — we don’t look much like kin. Walt is tanned and golden-haired from days upon days in the sunny tobacco fields. He takes after our mother, who was a looker. I take after our father, who was thin as a beanpole with a shock of red hair. “Carrot Top,” folks called him, and they called me that, too.

We dropped our bags at Flora Sorrell’s Boarding House on Main Street. We had enough money between us for one room, and Walt gallantly offered to sleep on the floor so I could have the single bed. We took turns washing our faces in the sink, and Walt changed into a fresh shirt.

For the Asheville Sessions I was wearing my second-best dress and Mama’s good cotton cloche with a pearl pin to keep it in place. It covered all of my hair except for the braid down my back. There wasn’t much I could do to disguise my freckles or gangly limbs.

Walt asked a man on the street for directions to the Vanderbilt Hotel. It was our first time in Asheville and I wanted to look around. There were tall buildings everywhere and ladies in fine dresses leading children by the hand. There were stores and restaurants, so many windows I wanted to stare into. But Walt was hurrying on ahead, his fiddle tucked under his arm. I gripped my carpet bag and trotted after my brother’s retreating back.

The Vanderbilt Hotel was red brick and many stories high. Seven or eight, I’d guess. And all around people were running here and there, everyone busy. Porters moving luggage, shiny automobiles parked along the curb, the desk clerk with his sleeves rolled up trying to keep track of it all. “You,” he shouted at Walt. “Are you with one of the bands?”

Walt was clever enough to say “yessir,” even though we weren’t. We’d just come on our own, uninvited, hoping to be able to make a record. But the desk clerk jabbed his fountain pen in the direction of the elevator and said, “Go up to the roof.” The elevator, too, was packed with people — some hotel guests and some musicians. I thought I might be standing next to Mister Fisher Hendley himself, the fiddler, and the idea of it left me so distracted I forget to pay attention to my first-ever elevator ride.

We walked up a final short staircase and pushed through a door onto the roof. There we were, up where birds soar, with the Blue Ridge Mountains just as far as the eye could see. The mountains were, indeed, a hazy blue in the distance. I imagined I could spot Waynesville if I had a minute to look, but Walt was calling to me, “C’mon Liza. Stick close and let me do the talking.”

I had no plans to do any talking, one, because I was often tongue-tied, and two, because I was just along for the ride. But I nodded and closed the distance between myself and Walt’s side. The recording laboratory was makeshift — something like a pillow fort built by a herd of children. The walls were hung with blankets in order to drown out some of the city noise, though we could still make out the faint sounds of car horns and people’s voices from Haywood Street below. The elevator rumbled occasionally, too.

Around the reproducing device, chairs were arranged for the musicians. Mister Bascom Lamar Lunsford himself was up there, holding his fiddle up to his chin. Not that I recognized him by sight, but when Walt said his name I recognized it from the recording we had of his — “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground.”

We sunk back into a corner, watching the whole operation. The engineer counting down, the wax platter spinning, and Mister Lunsford launching into a fiddle tune while his feet tapped out a rhythm. His shirt was dark with sweat, but his playing was fresh as a daisy and I found myself pulled from my own thoughts of perspiration dampening my second-best dress. I was enthralled with Mister Lunsford — how he was kind of a combination of Walt and me, what with the fiddling and clogging. But he wasn’t as sun-bronzed and inner-lit as Walt, and he couldn’t sing harmony with himself. That we had on him.

After the session ended and the men had shaken hands all around, Walt made his presence known. He smiled that broad white smile of his and doffed his cap. “Any chance you gentlemen have time to record another fiddle player today?” he asked.

They looked from one to the other, and the engineer finally said, “What do you think, Mister Peer?” in a sharp New York accent. I realized then the man in charge of it all was the record label owner himself. The one who put out the call for hill music. The one who could make Walt a star.

Mister Peer looked harried, sweat-damp and flush-faced. I could feel him wanting to say no — he’d perhaps bitten off more than he could chew with that roof-top recording session. But the engineer, who had a kindly face, said, “Our next band hasn’t arrived yet. You want to play us a song, son?”

I couldn’t help myself from blurting, “Go ahead and get your reproducing device ready, Mister. You’re going to love Walt’s playing.”

Mister Peer spun around, seeing me for the first time. “Who are you? This fella’s wife?”

I felt myself go red again. “No sir. I’m his sister. And I sing harmony.”

Walt shot me a warning look, but Mister Peer went quiet for a moment. “We haven’t had a brother-sister duo yet,” he murmured. “What are you called?”

“The Frog Level Family Band,” Walt said quickly, even though we’d never talked about it before. “I’m Walt Withers and this is my littler sister, Liza Withers.”

“Walt Withers and the Frog Level Family Band,” Mister Peer said, jotting something down in the notebook he pulled from his pocket. “Alright son, let’s hear what you got. What are you going to play for us?”

“Get Along Home, Cindy,” Walt said. It was one of our favorites — we’d played it a million times.

Walt and I made our way to the circle of chairs, but we didn’t sit down. Walt took his fiddle out and rosined the bow while I changed into the hard-soled boots I’d been carrying in my carpet bag. My dancing shoes. I gave a few tentative taps on the concrete floor, Walt bowed a chord, and then the engineer was counting us in.

Walt looked at me and held my eyes, like we were two little kids from Waynesville about to jump off a high rock into an ice-cold creek. And I felt that delicious certainty in my veins that as soon as we opened our mouths to sing our whole lives would change.

Then the wax platter began to spin, and Walt began to play, and my feet tapped out a rhythm of joy somehow perfectly in time with my thudding heart.

This work of fiction was inspired by the article Okeh Record’s Historic Session in Asheville, by Kent Priestly.